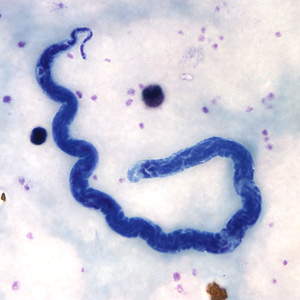

L. loa adult microfilariae

Overview[]

Loa loa is a parasitic nematode native to Central and Western Africa that is responsible for a condition known as loiasis. The first cases of patients with eye worms were in 1770, 1768, and 1777, and the manner of transmission remained a mystery until 1912 (Cox 2003). The parasite did not receive a name until 1913, and has only gained attention in recent years. There are few morphological differences between males and females, except that females can reach a maximum length of 70 mm, while males only grow to 34 mm (CDC 2010). Adults can survive in their host for 15 years or more (Harris 2003).

A variety of symptoms are associated with loiasis, but perhaps the most infamous is the worm’s ability to cross through the human eye and remain there for hours or even days, hence the nickname the African Eye Worm. Treatment for L. loa is difficult as the only effective treatment has potentially fatal side effects if the infection is too severe. The treatment is the same treatment used for most parasitic nematodes, thus complicating strategies of prevention and treatment for co-endemic nematodes such as Wucheria bancrofti and Onchocerca volvulus (Kouam et. al 2013).

Life Cycle[]

L. loa life cycle made by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention

A human becomes infected with the larval stage of L. loa when bitten by an infected Chrysops fly, usually of the species C. dimidiata or C. silicea (Kelly-Hope et. al 2012). The immature larva is deposited into the circulatory system and migrates to the lymphatic system shortly afterwards, disappearing from the bloodstream for the next 5-6 months. For the next 5-6 months, larvae mature into adult worms. Adult worms travel through subcutaneous tissue, living between layers of fascia and connective tissue, often at the extremeties and joints (Barua et. al 2005). L. loa adults reproduce sexually, and a single adult female may produce thousands of microfilariae per day which migrate into the bloodstream. The larvae are then ingested by the Chrysops fly when it feeds from an infected human. The ingested larvae invade cells on the fly’s abdomen where they develop to their infective stage. Once they reach their infective stage, they migrate to the fly’s mouthparts so they may be transmitted when the next blood meal is taken (CDC 2010). Larvae mortality is high and few ever make it to adulthood (Harris 2003).

Pathology & Symptoms[]

Photograph taken of the patient in the Case Report by Barua et. al 2005. L. loa adult can be seen migrating across the patient’s pupil.

The severity and combination of symptoms experienced by individuals presenting loiasis are extremely varied. Characteristic symptoms include Calabar Swellings and eye worm. Calabar are localized, non-tender swellings that are often quite itchy. Eye worm is visible migration of the adult worm across the host’s eye and is known to cause itching, pain, sensitivity to light, and eye congestion.

Other common symptoms include hives, muscle pain, joint pain, fatigue, peripheral eosinophilia, general itching, and inflammation of the lymph glands. Worms are known to visibly migrate under the skin, but their migration is less pronounced than in other species like Dracunculus medinensis . Long-term infection may be associated with kidney damage and scarring of cardiac tissue. Many of these symptoms, such as hives or inflammation of the lymph nodes, are the result of the immune response rather than the worm’s feeding, migration, or other behaviors (Harris 2003).

Many people do not experience any symptoms. Natives (endemics), however, are more likely to experience chronic but asymptomatic infections. According to Steel et. al in 2012, loiasis can interfere with normal T cell responses, causing more “allergic-type” reactions in non-natives (expatriates) with acute loiasis. Although research has begun, the cause of this is not yet fully understood.

Diagnosis[]

There are three options for diagnosis of loiasis: blood smear, antibody test, or analysis of Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) products (CDC 2010).

1. 1. Blood smears are analyzed for larvae. Because larvae are only released into the blood stream at certain times of day, blood samples must be taken from the patient between 10 am and 2 pm. Failure to do so will dramatically increase the likelihood of a false negative.

2. 2. Antibody tests are often performed as an alternative to a blood smear. However, this test cannot confirm if the patient has an active infection, only whether or not they have ever had loiasis at all.

3. 3. L. loa can be identified by analysis of PCR products, but only one test has been approved for use in the United States. Overall, blood smears are the preferred, most practical, and most accurate manner in which to diagnose a patient.

Due to severe side effects of Diethylcarbamazine (Ivermectin) on patients with loiasis, all patients requiring treatment for lymphatic filariasis should be screened for L. loa (Kouam et. al 2013).

Treatment and Control[]

C. dimindiata (above) and C. silicea can transmit L. loa. They go by many common names including Tabanid, Mango, Mangrove, Deer, Yellow, and Horse Flies

One treatment available is Albendazole, however, Albendazole is known only to kill adult worms. Therefore, Ivermectin is the more effective treatment. However, Ivermectin is commonly used in the treatment of other parasitic nematodes, such as W. bancrofti and O. volvulus. Without much knowledge of L. loa, efforts to treat W. bancrofti and O. volvulus began in 1999 by providing villages with Ivermectin en masse (Kouam et. al 2013). Although successful in many patients, severe and even fatal encephalopathy occurred in some. It was later discovered that Ivermectin treatment was lethal to almost all patients who had more than 30,000 L . loa microfilariae per milliliter of blood (Kouam et. al 2013). Thus, treatment and control efforts initially directed at W. bancrofti and O. volvulus

were complicated by the frequency of coincidence with loiasis (Kelly-Hope et. al 2012).

Findings from Kelly Hope et. al, 2012, demostrating the relationship of L. loa prevalence and ecological factors. A. L. loa prevalence and risk association based on location. B. A strict boundary defining the region with >40% infection rate. C. L. loa risk boundary vs. forestation. D. L. loa risk boundary vs. the Congo River System.

Ivermectin can be an effective treatment for loiasis, though it is risky. While no vaccines are available, taking Ivermectin once a week while in high-risk areas is a good prophylactic. This medication kills both adults and larvae and is the treatment of choice for patients with a low-density infection. It may be used on patients with high parasite density in the blood, but only if they receive proper medical attention prior to treatment. Proper preparation will dramatically reduce the rate of fatal brain inflammation (Kouam et. al 2013).

Prevention []

L. loa is present in 11 countries in Central and Western Africa. However the prevalence varies greatly, usually dependent on the environment. Depending on location, the local infection rate can climb up towards 90% of individuals infected (Kelly-Hope et. al 2012). The flies breed in high canopy forested, making villages on the periphery of the forests at the highest risk of contracting L. loa.

The simplest and most effective method of prophylaxis is to minimize the number of bites one receives from Chrysops flies (Kouam et. al 2013). This is best achieved by simply avoiding areas at high risk of loiasis. However, other personal protection methods include covering up as much skin as possible, wearing permethrin treated clothes, and wearing insect repellant (DEET is recommended) on exposed skin. If you suspect you are infected, it is best to get it treated immediately since large parasite density in the blood complicates treatment.

Recent Research[]

It has been widely observed that there is a great deal of variation in symptoms and chronicity for patients presenting filarial infections such as loiasis. Cathy Steel and her peers form the National Institute of Health in Maryland, USA, published a study in 2012 on the subject that suggests CD8+ cells are involved in important pathways that generate the seemingly “allergic” response of some patients. Expatriates most commonly experience these allergic reactions (i.e. Calabar Swellings, general itchiness, etc.) and while local populations chronically exposed to the parasite are often nearly asymptomatic.

They analyzed the global gene expression of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells (>5,000 genes) to determine what genes were being expressed by T-cells and in what quantities, thus shedding light on the physiology experienced by humans. By use of microarray they found that overall levels of expression were very similar in all but two categories: T cell response ex vivo and response to parasitic and non-parasitic antigens, which primarily manifested in differences in inflammatory response and regulation of cell death. Endemics were more likely to experience cell-induced apoptosis and a relatively minor inflammatory response. Expatriates displayed more activation induced cell death, increased inflammatory response, as well as elevated IgE levels (which are typically associated with allergic response). Steel hypothesizes that the variation in reaction could be related to exposure to parasitic antigens in utero.

Sources

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. (2010, November 2). Parasites - Loiasis. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/loiasis/

Cox, F.E.G. History of Human Parasitology. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2003 15(4):595.

Harris, M. 2003. "Loa loa" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed April 23, 2014 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Loa_loa/

Kouam, et al. Impact of repeated ivermectin treatments against onchocercasis on transmission of loiasis: an entomologic evaluation in central Cameroon. Parasites & Vectors. 2013 6:283.

Kelly-Hope, L., Bockarie, M., Molyneux, D. Loa loa Ecology in Central Africa: Role of the Congo River System. Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2012 6:6.

Barua, P., Barua, N., Hazarika, NK., Das, S. Loa loa in the Anterior Chamber of the Eye: A Case Report. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2005 23:1.

Steel, C., Varma, S., Nutman, T. Regulation of Global Gene Expression in Human Loa loa Infection is a Function of Chronicity.